It’s September 9th, the morning after the death of Queen Elizabeth II. I open the curtains to see a world that looks the same as yesterday but as I turn on the tele, every figure is a newsreader and I’m faced with the same facial expression repeated over and again. Switching to the internet, the face of a the queen, encased in deep black background pops up every other second as I scroll an article on something as far removed as can be imagined. There is no mistaking London bridge is down, the Queen is dead.

I was not alone in sensing the imminent likelihood of her passing, I know this much. The cues were there, news of heightened medical concern and her family heading from their varied corners to meet by her side. We know enough about death to know what this means.

Whilst the headlines speak of ‘a nation in mourning’, many of us know that rather than being how everyone feels; this is how everyone is ‘supposed to’ feel. It reads as a collective call to action (to cry, to mourn) with no time for outliers. Yet we might feel very differently depending on how we felt about the queen and the institution of royalty itself. Irrespective of how we felt about the queen, the news is likely to have stirred up some emotion inside of us. For a death is never really just about a singular event, but about all loss.

One of the things we saw from the outpouring of grief over Diana’s death was not just (and sometimes not at all) about how people felt about her character. The outpouring of grief could be seen as a mass expulsion of unexpressed individual grief, given a permissible social outlet, perhaps for the first time. In this public demonstration of grief, formerly unexpressed pain could be seen and heard. In a society where talking about mortality is taboo, such public deaths open a window for grief to breathe.

Celebrity and public figure deaths can be seen to bring death to the front of our awareness whilst also keeping it at a safe distance. There is a mediation that lets us tentatively tap into our sadness yet switch off (the tele) when we need to. The news tends to evoke grief from our own lives, reminding us of the loss of someone we loved, or imagining the last days of a loved one. Grief also arises with the anticipation and inevitability of loss when caring for a terminally ill loved one. Yet as we cannot live without love, we cannot evade grief. As Dr Colin Murray Parkes stated, ‘The pain of grief is as much a part of life as the joy of love, it is perhaps the price we pay for love’ (Murray Parkes, 1972) The queen would later go on to paraphrase Parkes, declaring ‘grief is the price we pay for love’ as she addressed those bereaved by the traumatic events of 9/11.

Declarations (although unfounded) that suggest ‘a nation in grief’ capture the collective task of grieving, yet obscure the individual task of meaning making. While we all grieve, grief is not a ‘one size fits all’ and we don’t all grieve the same way.

In her book ‘Atlas of the Heart’ (Brown 2020) Brene Brown recalls an intimate conversation with grief expert David Kessler Brown. She shares feeling deeply impacted upon hearing Kessler’s commentary that:

‘Each person’s grief is as unique as their fingerprint, but what everyone has in common is that no matter how they grieve, they share a need for their grief to be witnessed’

In grief then, what we need is someone to be fully present and able to bear our sadness without trying to lift our mood (Brown, 2020). This may look like someone sitting in silence next to us or offering a hand on our shoulder. It may look like someone letting us know they understand what we might be feeling while keeping in mind that this can only ever be estimation. Seeing someone we care about in pain can be very hard to bear and not try to ‘fix’. Yet grief cannot be fixed. It is in being fully present and witnessing another’s pain that connection comes, and through this connection, healing.

Grief is as wide as an ocean taking many forms and arising from many different situations. So often we have abruptly lost a connection with a loved one, and this severance can feel violent, disorientating, shaking our very sense of being in the world to the core. Grief can feel like having your heart ripped out your chest without anaesthetic, or being dumped onto another planet with no map home. It can be hard to see past the moment. W H Auden ‘Funeral Blues’ (1938) is a particularly poignant example of this:

Stop all the clocks, cut off the telephone,

Prevent the dog from barking with a juicy bone.

Silence the pianos and with muffled drum

Bring out the coffin, let the mourners come.Let aeroplanes circle moaning overhead

Scribbling on the sky the message He is Dead,

Put crépe bows round the white necks of the public doves,

Let the traffic policemen wear black cotton gloves.He was my North, my South, my East and West,

My working week and my Sunday rest,

My noon, my midnight, my talk, my song,

I thought that love would last forever: I was wrongThe stars are not wanted now, put out every one;

Pack up the moon and dismantle the sun;

Pour away the ocean and sweep up the wood.

For nothing now can ever come to any good.

Despite being a deeply personal account of loss, we can also see it as very much public, recognising grief as part of the human condition. There are few of us who cannot relate to the loss and accompanying emotional pain inherent in this poem. Auden here has created a coherent narrative in conveying grief to the audience. It is through relationships with others that we undertake the essential task of meaning making, trying to make sense of the senseless. Studies have shown the power of storytelling in healing (Bosticco, C. and Thompson T.L, 2005). In talking to another about your lost loved one, reflecting on your memories and personal bond, feelings are organised, felt and processed. Comfort can also be found in realising that it is the person (or beloved animal) that has died, not your bond, and creative ways can be found to keep a sense of the person with you that brings you comfort.

It can be useful to look at how grief shows up after bereavement. Brene Brown notes there are various ways grief appear, including the following:

Acute Grief: This occurs in the initial time after a loss. Here, sadness and longing tend to be felt intensely. Bitterness, anger, anxiety, remorse, guilt and sometimes shame can also be present. During this time, thoughts tend to be consumed by thinking of the lost loved one.

Integrated Grief: This reflects an adaption to the loss; the person is remembered in ways that no longer cause upset or distress. Here, Brown notes ‘Grief finds a place’ (Brown, 2022).

Complicated grief: This is grief that is hindered from being integrated. This grief is characterised by the presence of deep emotional pain, denial and hopelessness. The grief dominates everything, affecting relationships and making it hard to see a future beyond the death. It is a grief that is often mistaken for depression. Emerging from this grief can require professional help.

Disenfranchised grief: This is ‘unseen grief’. Here, others do not tend to recognise or acknowledge the person’s loss is an actual loss. Brown notes examples of disenfranchised loss include the loss of an unborn child, infertility, the loss of a parent due to separation and the multiple losses of being a survivor of abuse (Brown,2022).

Stigma is often all too present around this grief. As such I’d argue this kind of grief is disproportionately present in marginalised populations, such as Black and Brown and LGBTQ+ communities. A way we can see this is through the lack of compassion and justice when lives are taken through prejudice (e.g. Hate crimes and police murders), medical negligence (e.g. The Aids crisis) and the impact on loved ones and communities left in mourning.

Perhaps we can see Auden’s poem as an example of disenfranchised grief too, the poem tends to be read by a woman, thus obscuring the hidden devastation of the loss of the (Auden’s?) same gender lover. Of course, gender, sexual and relationship diverse people commonly face invalidation and lack of recognition over the significance of their relationships.

We might also think of the disenfranchised grief that comes with the loss of time and opportunities for those who were unable to realise and express themselves as gender and/or sexually diverse due to heterosexual, cissexual and mononormative norms for example. We also see it in those left in devastating limbo waiting on life changing decisions after seeking refugee from persecution. We see it in years lost through prison time through institutional racism and classism. We see it in lost childhoods due to family rejection/abuse. The loss of time many marginalised people face is deeply painful.

Disenfranchised grief can feel particularly hard to recover from as it is characterised by a lack of validation, a lack of being witnessed and heard by another. As we’ve noted, whilst grieving is felt individually and uniquely, it is healed collectively through relationship with others. Anyone who lost a loved one during ‘lockdown’ will know this only too well. The loss of community support can be deeply lonely and pretty unbearable.

Brown omits noting Anticipatory Grief; indeed this grief is frequently overlooked. Here we grieve while the person is still alive; feeling our sadness and loss as we prepare for a dying loved one’s death.

Many people find models useful in terms of understanding the process of grief. One of the most well-known is the Kubler-Ross’s Stages of Grief model (Cruse 2022) which suggests stages of Denial, Anger, Depression, Bargaining, and Acceptance. This is particularly helpful for those who are facing death but less useful for loved one’s. It’s also been misinterpreted as suggesting a linear process when as Kubler-Ross notes, people in fact tend to move in and out of the stages randomly and some stages not at all.

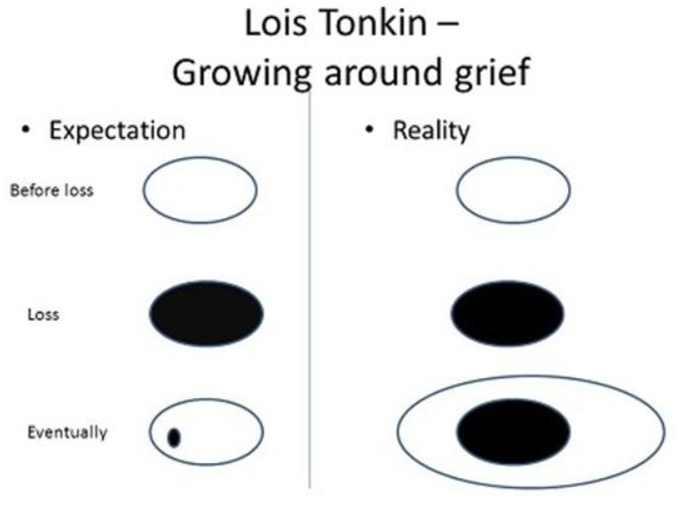

Tonkin’s ‘Growing around Grief’ (Cruse 2022) model is a good depiction of how we integrate a loss. Rather than ‘getting over it’, we grow around it. As you’ll see in the picture grief doesn’t shrink or go away but we find a way to adapt to the loss. Starting to have new experiences again such as making a friend or joining a course are examples of growing around grief.

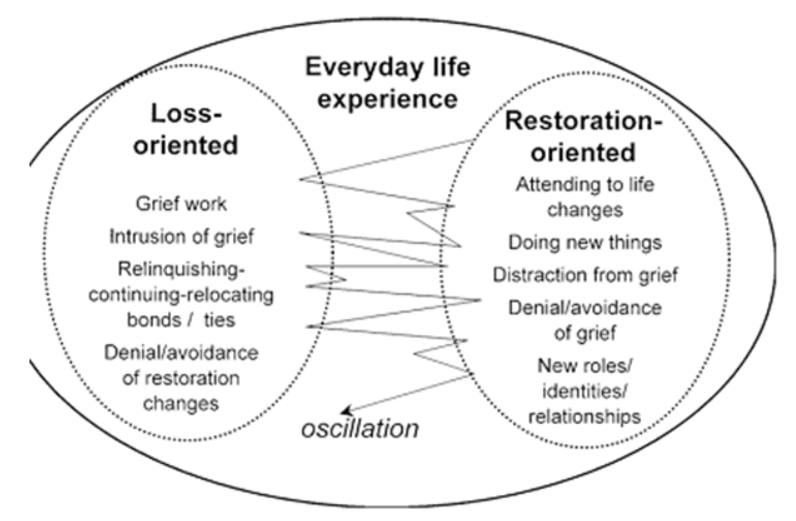

Stroebe and Schut present the Dual Process model of Coping with Bereavement (What’s your grief 2022) to illustrate that people tend to oscillate between living in the past and looking towards the future. Life will feel like ‘up’s and down’s’ before it begins to settle, hopefully into integration.

Stroebe and Schut present the Dual Process model of Coping with Bereavement (What’s your grief 2022) to illustrate that people tend to oscillate between living in the past and looking towards the future. Life will feel like ‘up’s and down’s’ before it begins to settle, hopefully into integration.

The Dual Process Model of coping with bereavement by Stroebe and Schut:

William Worden (2008) developed ‘Tasks of Mourning’ (Psychology today, 2019) which is a helpful model to understand the practical aspects of adjustment. These tasks include:

William Worden (2008) developed ‘Tasks of Mourning’ (Psychology today, 2019) which is a helpful model to understand the practical aspects of adjustment. These tasks include:

- Acceptance (of the reality of the loss)

- Processing (the pain of your grief)

- Adjusting (to the world without the one who has died)

- Finding (ways to keep the memory of the lost one while still moving forward with life).

Through my work as a therapist I’ve seen really creative ways that people fill this latter task, such as starting up a hobby that the person they loved enjoyed, or finding themselves incorporating a mannerism, or outlook on life of a loved one. This can be seen as an example of Post Traumatic growth (Psychology Today,2022).

Worden noted that factors such as the nature of the death, extent of the attachment, concurrent stressors, life experiences and individual psychological make up all shape a person’s response to loss. Although Worden doesn’t mentioned community support here, we cannot underestimate the importance of emotional and social support from others. It is essential to healing that grief is acknowledged, heard and witnessed by others. Given this, you might be finding it incredibly hard if you are socially isolated and/or experiencing disenfranchised grief.

Many people find the models above useful in that they offer clarity, and perhaps reassurance when trying to adapt to a painful loss. Hopefully they have been helpful to you too. Ultimately grief is super hard, hurt can’t be captured by models and words can barely scratch the surface. Yet I hope this post can sit alongside you quietly and put a gentle hand on your shoulder when you need it.

References

All Poetry (2022) Funeral Blues by W H Auden Available at: https://allpoetry.com/Funeral-Blues (Accessed: 14th September)

Bosticco, C. and Thompson TL. (2005) ‘Narratives and Story Telling in Coping with Grief and Bereavement’ 51(1) Research Gate. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/247871286_Narratives_and_Story_Telling_in_Coping_with_Grief_and_Bereavement. (Accessed:17th September 2022).

Brown, B. (2021) Atlas of the Heart-Mapping Meaningful Connection and the Language of Human Experience. U.S. Penguin Random House.

Cruse, (2022) Growing around Grief. Available at: https://www.cruse.org.uk/understanding-grief/effects-of-grief/growing-around-grief/ (Accessed 15 September 2022).

Cruse (2022) Understanding the five stages of Grief. Available at: https://www.cruse.org.uk/understanding-grief/effects-of-grief/five-stages-of-grief/ (accessed 17th September 2022).

Parkes, C.M and Prigeerson H.G. (2010) Studies of Grief in Adult Life. 4th edn. UK. Routledge

Psychology Today, (2022). Post Traumatic Growth. Available at: https://www.psychologytoday.com/gb/basics/post-traumatic-growth (Accessed: 14 September 2022)

Psychology Today (2019)The Four Tasks of Grieving. Available at: https://www.psychologytoday.com/gb/blog/mental-health-nerd/201911/the-4-tasks-grieving (Accessed: 16 September 2022)

What’s your grief (2022) Grief Theory 101: The Dual Process Model of Grief. Available at: https://whatsyourgrief.com/dual-process-model-of-grief/ (Accessed: 17September 2022)

Image Credit

By gadiellv. Licensed under Creative Commons