It’s a warm Sunday evening and I’m coming to the end of another Netflix show. The weekend started with the glorious ‘The Half of It’ and ended with Rupaul’s Celebrity Drag Race, passing through Maniac and A Secret Love. Despite the mix of genres, one thing stood out for me: they were all about connection and the pain of being without it. All involved love stories; yet the primary love story was the relationship with the self. It was the act of accepting and standing by one’s self.

Throughout these stories, people made attempts to navigate social stigma and exclusion around aspects of themselves such as their mental health, ethnicity, gender and sexual expression. All could be seen to be experiencing minority stress.

In all, there was a clear sense of isolation, of being on the outside. Yet these are the stories of people who’ve had found a way to accept themselves through positive relationships with others who embraced them for who they were. Indeed, there is the idea in relational based therapy that if we are harmed in relationships with others, then we are also healed in (positive) relationships with others.

Humans are social beings. As such, we need to connect with others for our mental and physical survival.

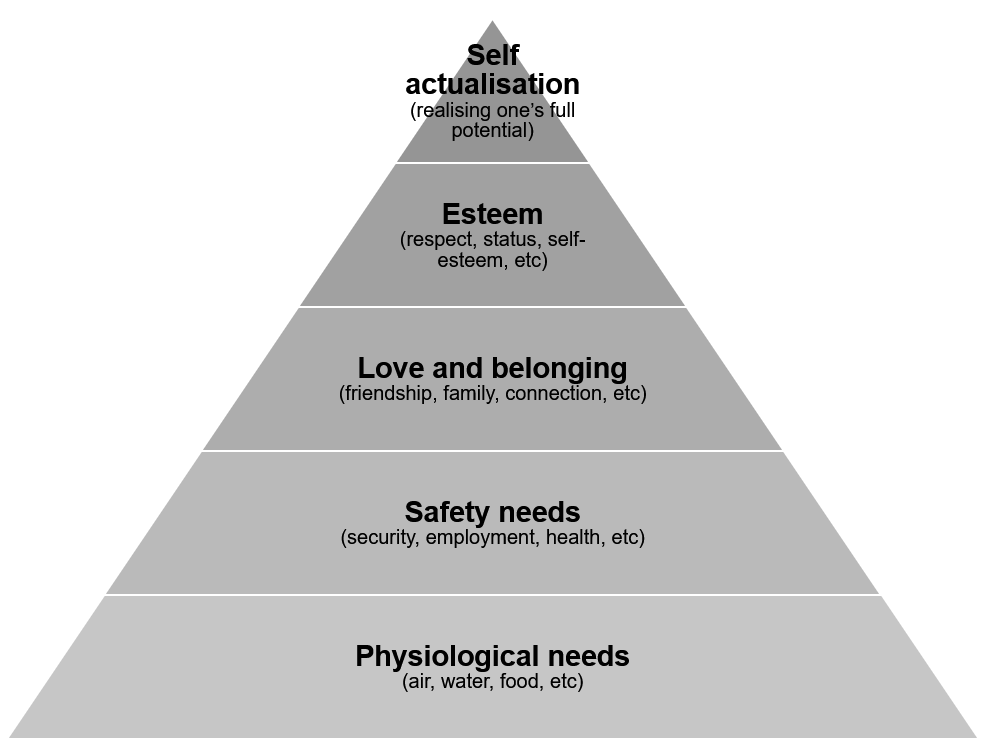

In Abraham Maslow’s (1943) ‘Hierarchy of Needs’ model below, we see the importance of not just of physical needs being met, but also emotional needs. This includes a sense of love and belonging through intimacy and connection to others. We also see from the model that fulfilment of this (social) need is necessary in order for us to have decent self-esteem and view ourselves as worthwhile. We are interdependent.

We are born into relationships. We learn to perceive ourselves through others from a very young age. We become attuned to understanding what is acceptable, our own self-worth and whether we can depend on others. As we grow and encounter other people in our lives, we further develop a sense of our own identity and self-worth through our relationships. In fact, social survival depends on acceptance from peers. This usually involves compromising some aspect of the self in order to conform to a group norm and be accepted. In this sense, we all lose something, some part of our selves, in order to gain the rewards of group acceptance, of being on the inside rather than the outside. How much we lose depends on how close the fit is between us and the group norms (which usually reflect society’s dominant norms). Social acceptance can feel like life or death.

For example, young people seek to reduce any sense of difference from the group and this can mean disavowing important aspects of their experiences and identity. We see this in boys replacing tears with rage as this is the only permitted emotional expression, in girls suppressing their sexual desire to avoid being labelled; and in gender-variant young people hiding their ‘queerness’.

All this tends to lead to disconnection with the self as we push away those ‘unacceptable’ parts our selves. This sense of being unacceptable results in shame and as this is such a painful feeling to bear, it gets pushed deep down (only to re-appear years later as feeling ‘embarrassed’ or ‘uncomfortable’). Nonetheless, we may grow, but with a sense of worthlessness. We struggle to know ourselves and to connect as it feels (and can be) unsafe to show our true selves.

Social shaming may come from adults as well as young people. Too often, the young person is held responsible for not ‘fitting in’, for ‘standing out’ from the crowd, and bullying is condoned and even led/joined in by some adults. This can lead to feelings of self-hatred, depression, social anxiety and fear of relationships with others. This is relational trauma.

There is the argument that trauma experienced through a social relationship causes greater devastation than that of a natural event such as a hurricane. This is due to the devastation of trust, the shaking of faith in humanity, the challenge to our core beliefs about the world. We may ask how we can trust another human again.

As a counsellor, I regularly see the affects of relational trauma in the therapy room. This often manifests as struggles around low self-esteem, self-loathing, social anxiety, depression, loneliness, suicidality and difficulty maintaining relationships. So often the root experience is isolation, a painful disconnection from others.

Effective therapy tends to involve a sense of connection between two human beings, an experience of being seen and accepted by another. Revered counsellor Carl Rogers (1957) argued that therapeutic change happens when clients feel heard, seen and understood just for who they are. He called this condition Unconditional Positive Regard (UPR). Mick Cooper and Dave Mearns (2005) asserted that effective counselling relationships often involve working at ‘relational depth’. This involves moments of genuine and deep connection between counsellor and client. We can see here that counselling is very much about the quality of the relationship. Just like all significant relationships, we both change, and are changed by the other. The pain of disconnection is soothed through this exchange.

Watching Rupaul’s Celebrity Drag Race I was moved to hear how the celebrities being mentored by the show’s drag queens where transformed not just physically but emotionally. A heterosexual masculine man noted he felt ‘beautiful’, ‘liberated’ and ‘in touch with my feminine side’. Another celebrity broke down and shared her pain of social exclusion and isolation due to racism and fatphobia and how this had devastated her self-esteem. One drag queen shared that their own preconceptions (borne from social rejection) around heterosexual men had been challenged.

When writer and producer Patrick Somerville was interviewed about the show ‘Maniac’, he noted:

‘Yes, the show’s about connection and it’s about friendship and about the ways that people can help each other, but you can’t even get there unless you can accept some things about yourself. You can’t make a connection with another person unless you can accept who you are in the first place’

This sounds similar to Rupaul’s notorious catch phrase:

‘If you can’t love yourself then how the hell you gonna love anyone else?’

Self-respect and self-acceptance are crucial to our physical and mental wellbeing. But do we really need to accept ourselves first before others can? As interdependent beings we are always within social relationships; we are both harmed and healed by them. This is why things like prejudice hit our self-esteem so hard and why we can find connecting with similar/supportive others so restorative. Often, the care of others can help us to come to know and accept ourselves. In fact, recent neuroplasticity research (Adlaf, et al., 2017) highlighted that the brain literally changes and creates new neural pathways through positive loving relationships, so much so that healing can be seen in the brains of people who have experienced severe abuse. Connection literally heals.

At the time of writing, voices are coming through expressing the pain of having no human touch for months. Others share the joy of a few minutes chat with the person on the tills at a local supermarket – separated by a physical barrier but connected by a sense of similarity of experience. Every day lately, we are confronted by the impact of inequality and social exclusion caused by health vulnerabilities, where factors such as age, poverty, disability and ethnicity can lead to significantly challenging individual experiences. We are observing ripples of compassion within our neighbourhoods and beyond. As the global trauma permeates our consciousnesses, reminding us just how truly connected our lives are, it seems that while physically-isolated, we are craving and understanding the importance of connection now more than ever.

Bibliography

Adlaf, E.W., Vaden, R.J., Niver, A.J., Manuel, A.F., Onyilo, V.C., Araujo, M.T., Dieni, C.V., Vo, H.T., King, G.D., Wadiche, J.I. and Overstreet-Wadiche, L., 2017. Adult-born neurons modify excitatory synaptic transmission to existing neurons. Elife, 6(1), p.e19886.

Maslow, A.H., 1943. A Theory of Human Motivation. Psychological Review, 50(4), pp. 370-396.

Mearns, D. and Cooper, M., 2017. Working at relational depth in counselling and psychotherapy. London: Sage Publications.

Rogers, C. R., 1957. The necessary and sufficient conditions of psychotherapeutic personality change. Journal of Consulting Psychology, 21(2), pp. 95–103.

Image Credit

By morteza_yousefi_ Licensed under Creative Commons